by Chuck Fager

A cargo airliner whose owners are only known to fly for the CIA, refeuling at the Shannon, Ireland, International Airport. There have been many protests against such CIA flight stopovers in Ireland. Photos by Chuck Fager |

Will government-sponsored torture remain a shocking anomaly in U.S. public life? Or will it become an accepted precedent, one of the many tools of power in the hands of our rulers?

I believe the United States is approaching a crucial shift from the first state to the second. It can be called the torture transition.

As this is written, our rulers have built Guantanamo, Abu Ghraib, a string of secret gulags, and a vast clandestine infrastructure to support them. Their inmates, who number in the thousands, have no legal protections. As the outlines of this system of suffering have been revealed, its architects have trumpeted their open and flagrant defiance of our own laws, international treaties, and the preponderance of informed world opinion.

I spent six weeks in Europe last spring, giving talks about the need for international action to dismantle this torture system. Along the way, I got a taste of just how repelled most thoughtful people on that continent are by this sordid spectacle. And while there, I came to understand better the torture transition and the importance of stopping it.

To be sure, each country I visited has its own shameful history of torture and abuse. Yet the reactions I experienced are not to be confused with hypocrisy. These people know their own countries’ failings well enough. That’s part of the reason for their dismay: they expected better from the United States, the self-proclaimed bastion of freedom and justice.

Nevertheless, most of those I spoke with were holding their breath, and still are, waiting for the rapidly approaching change of administration in Washington. Things are certain to get better then, they seem to feel; how could they possibly get worse?

I’ll tell you how. Things could get worse if the U.S. makes the torture transition.

What’s that?

The answer can be summed up in two words: impunity and precedent.

Impunity means getting away with it. If those who created the torture system and those who managed it are not held to account, they will have achieved impunity, which is now their primary goal.

The "torture transition" is coming nearer, day by day.

And with impunity will come a shift in the underpinnings of torture. It will move from being an outrageous aberration in our public order to being an accepted part of it. It will become precedent. With that change, all the laws and treaties against torture will be worthless, dead letters.

How does this work?

A homely local example will serve. At Quaker House, in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where I work, there is a sign in the front yard that says, as you might expect, “Quaker House.” It and its predecessors have been there for more than 35 years.

But this sign is in fact illegal. It openly violates local ordinances for residential neighborhoods like ours.

Nevertheless, because it’s been there so long without challenge, it has de facto become legal over time; the term of art is that it is now “grandfathered.” Fayetteville’s ordinance still stands, but so does our sign. We’ve gotten away with it; our sign has achieved impunity.

The same thing could happen with torture, even though—from various reports I’ve seen and heard—there is a good chance that the new President will say that torture is bad and that it will now stop.

Such an action would be good as far as it goes. But it could well mean no more than if, for instance, someone took a weapon that had been used in deadly assaults and put it away in a drawer.

It will still be there, at the ready, when—not if—the temptations of power begin to make the new ruler’s hands itch to use something “more effective,” when pushed to revisit the dark side, and pressed to use it to head off some new forecast of the so-called “ticking bomb” scenario.

If we think a new President, especially one many of us might support, would never do such a thing, I suggest that this is an overly optimistic view.

The weapon of torture will still be there. And next time, if the current perpetrators achieve impunity, it can be used again without hope of restraint. Torture will have been grandfathered into our system as surely as the sign on the Quaker House lawn.

Dick Marty, a Swiss senator and investigator for the Council of Europe, whose reports lifted the curtain on European governments' involvement in torture flights |

That’s the torture transition. And it’s coming nearer, day by day.

So what are the chances for impunity? How likely is it that those responsible for the U.S. torture machinery will escape punishment?

According to a man named Dick Marty, right now the chances are good. Very good, in fact.

Dick Marty should know. He’s the Swiss equivalent of a U.S. Senator—and the chief anti-torture investigator for the Council of Europe.

Marty produced two groundbreaking investigative reports that disclosed many hidden details about illegal U.S. torture flights to and across Europe. The reports named Poland and Romania as the sites of similarly unlawful secret U.S. prisons. And Marty charged that the UK had permitted torture flights too—a disclosure that proved correct despite initial government denials.

These reports are now available in book form, under the title CIA above the Law? Secret Detentions and Unlawful Inter-State Transfers of Detainees in Europe, published by the Council of Europe. At $46, the book is pricey, especially because of the decline of the U.S. dollar—which has weakened along with our international reputation. You can still find the reports online, though, for free at “The Council of Europe: Marty’s First Report” and “The Council of Europe: Marty’s Second Report.”

The CIA shrugged off Marty’s reports, and they got little play in the U.S. But elsewhere they are recognized as landmarks, and they haven’t exactly burnished the U.S. image abroad.

While in Europe, I sought an appointment with Dick Marty. Having done some investigative reporting myself, I wanted to pay respects to the author of such a superlative piece of work. More important, I hoped to get his candid view about the torture transition and what to do about it.

We met in his simply furnished office in the stunning city of Lugano, which hugs the shore of a sparkling lake in southern, Italian-speaking Switzerland. Its alpine serenity made a sharply incongruous backdrop for talk about such a grim subject.

Marty himself was informal and mild-mannered, his English limited. But his understanding of the subject was as sharp as I expected.

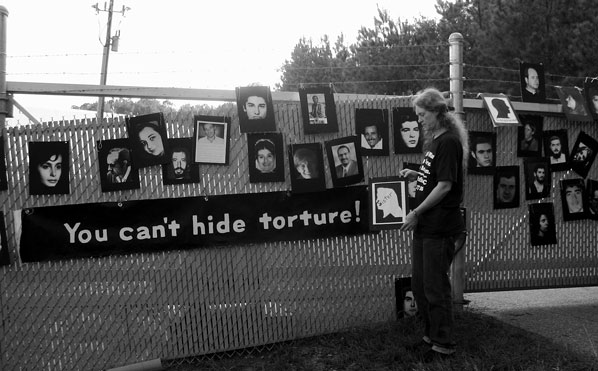

A protest banner outside Aero Contractors in Smithfield, N.C., October 2007 |

Without much in the way of introduction, I laid out my key query: Given what he knows, is there any way to stop the torture transition? Or would the perpetrators skate off into the sunset on rollerblades of impunity? (Pardon the amateur crime-fighter argot, but it fits; before Marty ran for the Swiss parliament, he was a tough prosecutor who bested mobsters and drug barons in his home canton of Ticino, which adjoins Italy.)

Marty’s response was unmistakable: “That’s exactly the right question to be asking,” he said.

After that he didn’t have much encouragement to offer, but he’s not in the optimism business. Sure, he agreed, torture is a crime under both international and national treaties and statutes. We don’t need any new laws.

But at a secret NATO meeting in Athens in late 2001, he told me, the U.S. demanded and got assurances of impunity for its military and intelligence agencies for any actions related to the “war on terror” on their territories. Several non-NATO nations, such as Ireland, later signed on as well.

On the home front, repeated government assertions of the doctrine of “state secrets” have thus far stymied efforts even by certifiably innocent torture victims to gain any redress. So, right now, it looks like a lost cause: tough luck, torture victims. And as for lovers of the Bill of Rights: better luck next time.

But Marty wasn’t suggesting I just go home and give up. “This will be a long work,” he said. “It will require patience and determination.” Which means that the current forecast for torturers may be sunny, but, like the weather, that can change.

How? In a lot of ways, mostly a bit at a time.

Here’s a scenario. Pressure keeps building in many countries for investigations of torture. This includes the U.S. after a new administration takes office in January 2009, driven by anti-torture groups and a growing list of their allies. Reporters keep disclosing ugly aspects of the torture structure and the efforts of its architects to achieve impunity. Public opinion begins to shift away from support for torture.

In several other countries, these probes eventually produce legal actions, including lawsuits and criminal complaints. (Reliable reports say that cases are already being prepared in several countries, to surface beginning next January.) And maybe the next President might just decide to keep out of their way.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and other defendants resist and evade the actions, some successfully. But sooner or later, one or more of them makes a misstep. For instance, they travel to a country that honors an outstanding warrant, and the police are waiting.

Behind the fence, at Aero Contractors |

If you think this scenario is too far-fetched, think again. Something very much like it happened in the most famous anti-impunity case so far: the arrest of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in London in October 1998. Pinochet was detained there for over a year, and his arrest gave a great impetus to anti-impunity efforts back home in Chile.

But to make anything like that happen in the U.S., where would such a buildup of public pressure come from?

Believe it or not, the most likely place is U.S. churches. There are already several interchurch anti-torture coalitions at work here. Numerous monthly and yearly meetings have joined in, adopting minutes opposing torture. The Quaker Initiative to End Torture has held two conferences on the subject.

Nor are these stirrings limited to the usual liberal suspects. There’s now a group called Evangelicals for Human Rights, based in Atlanta, which has persuaded some heavy hitters in that constituency to sign on and speak out.

All this is encouraging. But even so, Dick Marty’s sober counsel still rings in my mind. Torture is a subject that sends chills down the back for large numbers of us. For too many, those chills freeze the action response. Denial takes over; energy flows to other, less unnerving issues.

That’s been the response in many churches. And thus far, Friends are no exception. It’s been relatively easy for Quaker anti-torture workers to obtain minutes from meetings. But these are merely—pardon the expression—pieces of paper. It’s been much harder to gather a focused, working committee of Friends who are under the weight of this concern and carry leadings for long-term work. Such focused groups have been the necessary nucleus of just about all the best Quaker campaigns over the centuries. We’re still waiting for one to emerge in this effort.

This lag worries me. The stakes in the struggle are extremely high. If the torture transition comes to pass, torture will be regularized in U.S. governance. Our rulers will have effectively gained the ability to declare any citizen outside the protection of the law. And they can do that from above and beyond the restraints of the law, with impunity.

Those two powers—first, to declare any citizen outside the law’s protection, and second, to do so without fear of the law’s restraints—are the essential components of a police state, the pillars of tyranny. That is why I believe in making the prevention of impunity and stopping the torture transition top priorities for work against torture in the coming years.

The torture transition won’t be achieved in one bold declaration; that would risk rebellion. Instead, as it has been coming in recent years, it will advance incrementally, step by step, camouflaged by the rhetoric of “national security,” and hidden behind secrecy wherever possible.

Likewise, this transition will not be halted by any one massive act of protest or by a single election. If impunity is stopped, it will also be bit by bit, case by case. After all, once Augusto Pinochet yielded power in Chile in 1988, it took ten years of persistent work before Scotland Yard showed up at his door in London. Along the way, the Catholic Church was a major factor in breaking through the walls of impunity he tried to build around himself and his minions.

In this kind of work in the U.S., steadfast Friends can join with others to play a significant role. The early phases will not be dramatic: the gathering of an active and rooted Quaker committee; conferences, workshops, and other educational efforts among Friends; building connections with other human rights groups to multiply our impact; and keeping it up for the years to come.

The two Quaker conferences on torture were an excellent start, but the work since has lagged. I hope it will soon be relaunched in the focused, ongoing way called for by the gravity of the task it faces.

When it is, I plan to send Dick Marty a postcard. (How do you say “patience and determination” in Swiss-accented Italian?)

No comments:

Post a Comment